Japanese filmmakers and their filmmaking industry has been a prominent one in the international filmmaking arena since the second half of the 20th century. Slowly paced narrative than most films from other parts of the world, Japanese cinema has a distinctive look and feel. Heavy use of naturalistic/solar lighting, alongside low contrast, pastel colour grading are something the industry has pioneered over a long time. Such, combination of the above-mentioned aspects has allowed them to portray the themes of melancholy and ennui more visually and consistently than anyone else.

Filmmakers such as Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Akira Kurosawa, Hayao Miyazaki, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Shunji Iwai, Satoshi Kon, Sion Sono and more, have all made their marks on both the Japanese and international cinematic landscapes. Although just as acclaimed everywhere, one name that eludes most when it comes to prominent Japanese filmmakers is that of Takeshi Kitano. Kitano was a noted comedian and actor before he turned his attention to writing and directing his own films. For the majority of his career, Kitano worked exclusively in the Japanese Gangster genre of films; but there is one notable exception in his filmography - 1999’s Kikujiro.

Brief Summary

Kikujiro follows an 11-year-old boy named Masao. He lives with his maternal grandmother and the identity of his father is unknown. His mother does not keep in touch, and he has not met her in almost 10 years. During his summer vacation, without his grandmother's knowledge, he sets out to meet his mother based on an address he found of hers via happenstance in his grandmother’s drawer. But an earlier neighbour of his finds him in a precarious situation early in the journey and she enlist her reluctant husband to accompany Masao on his journey. Masao, being an introverted, shy child, agrees to every decision his impulsive ‘partner-in-crime’ makes.

The premise of the film resembles that of the Brazilian film Central Station by Walter Salles, released the year before Kikujiro. While the former ends shortly after reluctant the duo reaching their destination, Kikujiro subverts that trope of road trip genre of films. At around the midpoint of the film’s runtime, Masao and his partner arrive at their destination and watch his mother from a distance, only to find out that she has a different family of her own including another child. Broken-hearted, they travel back to their home town. The remainder of the movie deals with Masao’s partner and the people they meet, trying to cheer him up and mellow out the trauma he suffers. The film ends right after they reach back home. Masao watches his partner walk away for a few seconds, he then calls out to the older man. He asks what his name is. His partner, played by Kitano himself, yells gleefully “It’s Kikujiro, you idiot! Now scram!”. Masao runs back home, while Kikujiro watches him mournfully. Joe Hisashi’s beautiful theme song for the movie plays through these scenes, and as audience we root for the fact that this is not the duo’s last meeting and they live outside the boundaries of the narrative.

Cut to credits.

Short Analysis

Following the tradition of most films, Kikujiro woefully fails both the Bechdel and the Mako-Mori tests. There are only four women in the film who are given more than 10 seconds of screen time or dialogues, and they can only be categorised as minor characters at best. On the other hand, Masao and Kikujiro meet a variety of colourful men on their way and back. Three side characters with significant screen time are credited and are called within the story are Fatso, Baldie and the Travelling Man. Surprisingly enough, they all have more dimensions than most one-note characters in other films; and are empathetic to Masao’s trauma.

Different manifestations of masculinities are portrayed by each character, with most care given to Kikujiro himself. Typically, men empathising and trying their best to comfort another man, whether it be a child or an adult, is rarely portrayed in the silver screen. Conflicts between men are given more significance than relating with one another. While there are scenes which are outliers, Kikujiro and Kikujiro & gang are a wonderous subversion.

Kikujiro and His Complex Shades of Masculinities

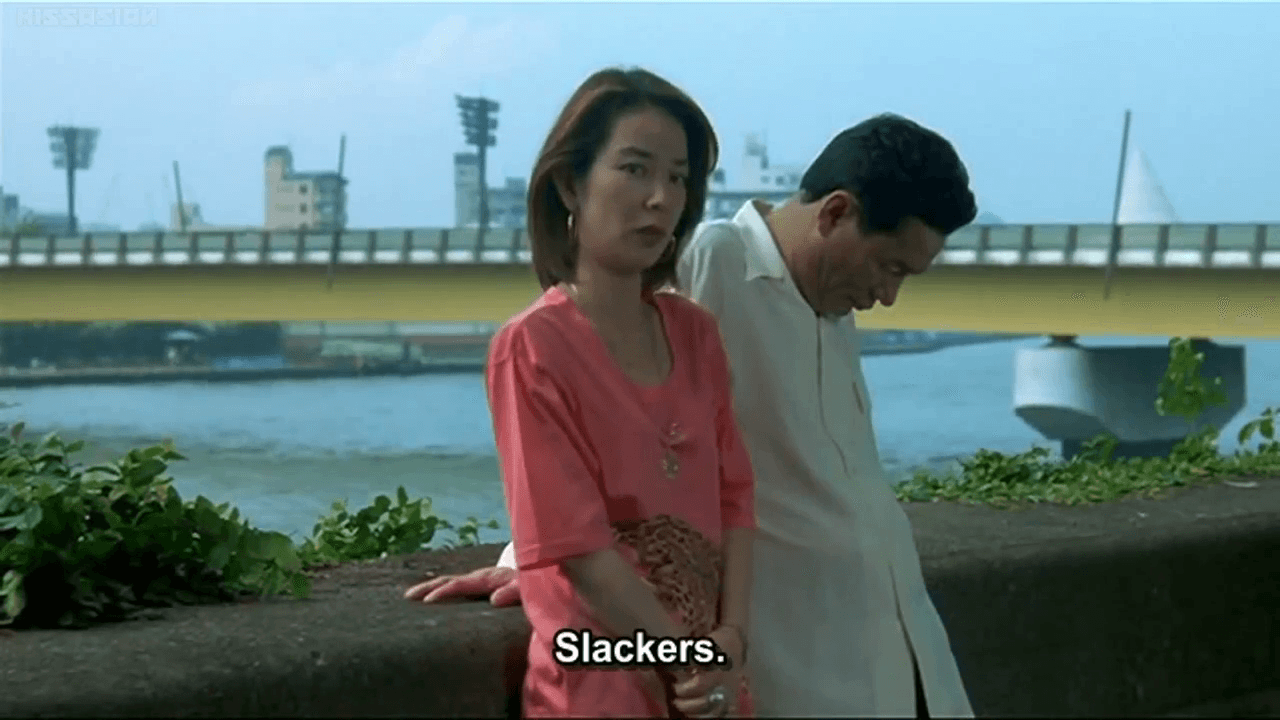

Pic. 01; Kikujiro behind his wife.

Here is the first time Kikujiro appears on screen. His wife is framed at the centre, with him standing ‘behind’ her. She yells at a group of high school students who are bunking their classes to casually hangout and smoke cigarettes. She warns them to do better or else “You (the students) will end up like him (she nods to Kikujiro)”. He stays silent and is even shown to be slightly scared of her in all the scenes they are together.

Pic. 02; Masao discovering Kikujiro’s tattoo for the first time.

Throughout the movie the film hints that Kikujiro might have had a past among the Yakuza (Japanese gangsters). This is mostly apparent when Masao sees Kikujiro shirtless beside a pool, and his entire back is covered with a traditional tattoo of a demon. Since in Japanese society having such tattoos are rather common among and is a distinct identification of Yakuza members, we can also assume that Kikujiro is/was part of a Yakuza.

He often shouts at people and acts stubborn. Most people give in to his antics and demands since his demeanour comes off with a threatening aura. He gives very little concern for the safety of Masao. In one scene he leaves Masao outside a bar while drinking alcohol. When he comes out of the bar, Masao is not there anymore. Someone mentions that the child left with another gentleman. Kikujiro frantically looks for Masao, and finds him behind a public toilet, where a middle-aged man is forcing Masao to strip his clothes. Kikujiro takes Masao away, and then promptly goes back to assault the paedophile. Aside from a few scenes, Kikujiro tries to not leave Masao unsupervised throughout the rest of the film.

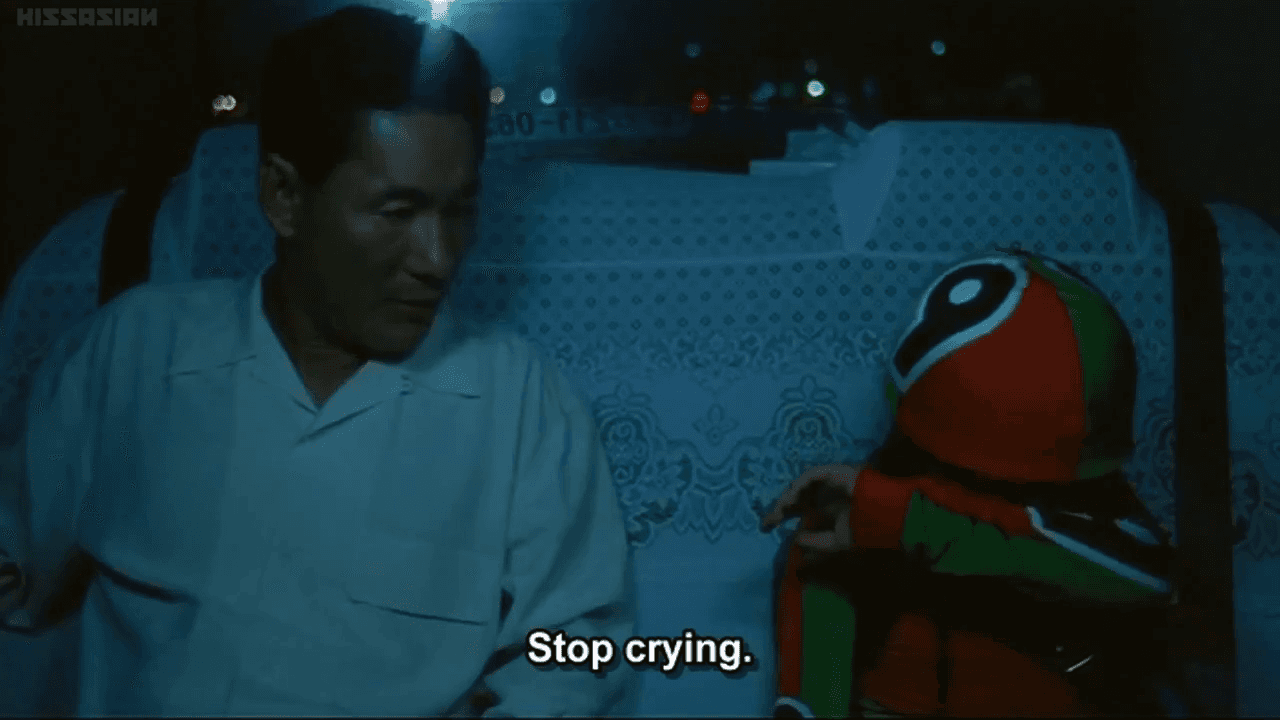

Pic. 03; Kikujiro trying to comfort Masao and asking him to stop crying.

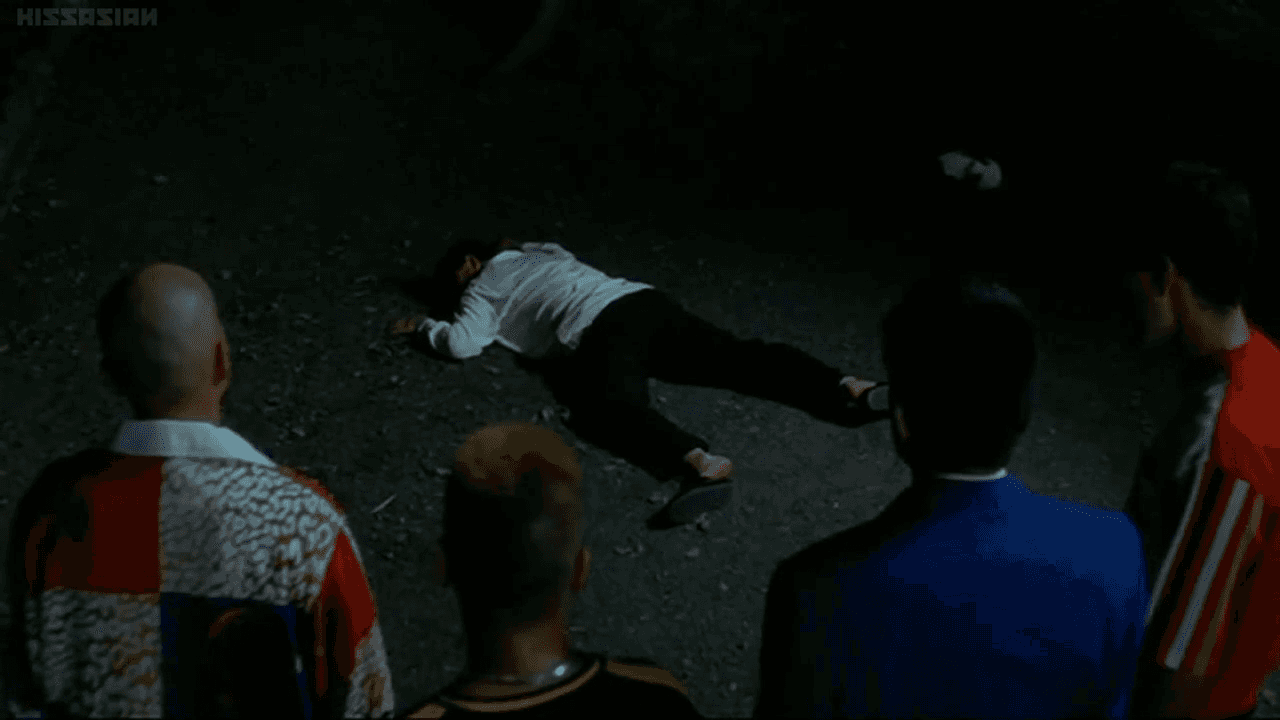

Pic. 04; A beaten up Kikujiro.

Pic. 05; Kikujiro lying unconscious surrounded by the gangsters who beat him up.

Unlike in his later films such as Zatoichi (2003), Kitano does not characterise the titular character in an almost superhero-ish manner. Though a Yakuza at some point, he cannot defeat everyone; like the way he did earlier to a trucker who had disagreements with him. Just before he is beaten down away from the earshot of Masao, Kikujiro taunts and even agrees to go fight the gangsters. Only after he realises that he cannot fight his way out does he say that he has a ‘child’ to take care of. But at that point the gangsters do not care for his excuses and knock him unconscious (it should be noted that there exists an element of slapstick in the manner Kikujiro is framed in Pic. 05).

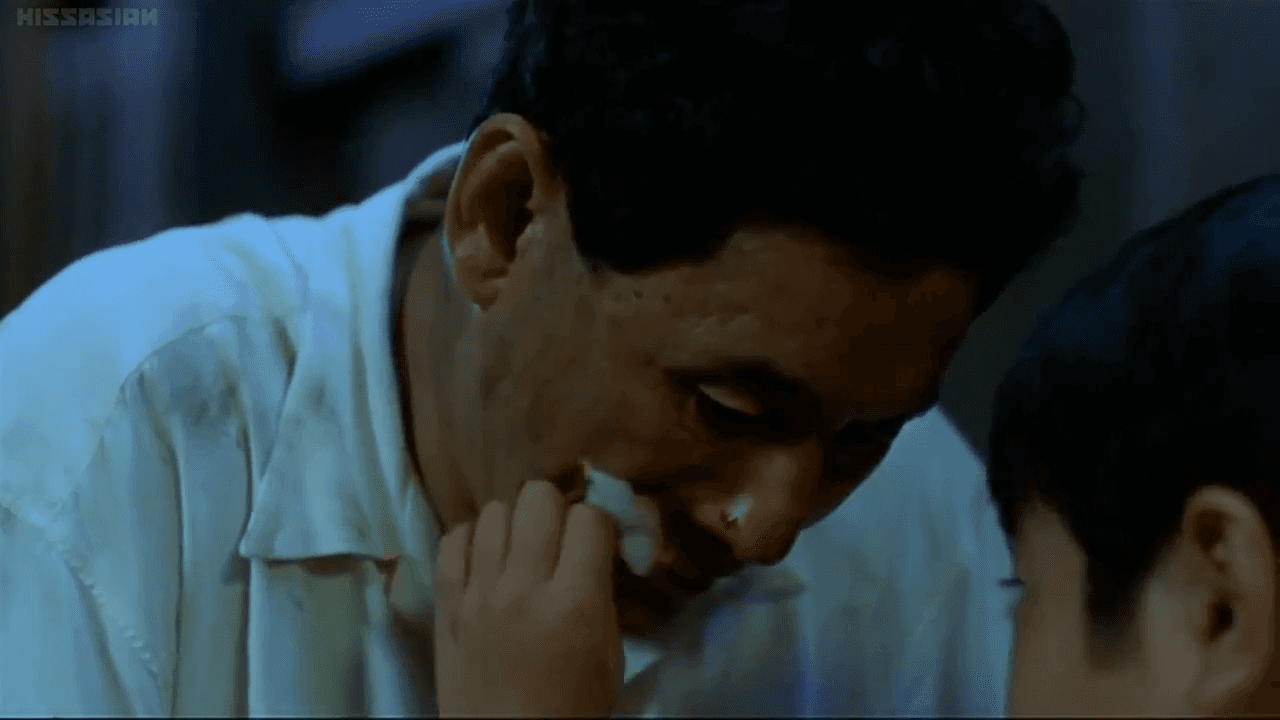

Pic. 06; Kikujiro sitting next to Masao after waking up from the beating.

Such, the threatening aura he has cultivated around him not only comes from him being a Yakuza, but it also functions as a defence mechanism for him to stand up to other people who may or may not be a threat to him. It also comes from this place of wanting to appear on top of everything at all times, as patriarchy demands from men. Particularly, in the scene right after coming back to Masao after getting beaten unconscious, Kikujiro acts as if everything is fine and tries to reassure the concerned child sitting next to him; even though Masao can see the blood slowly dripping off.

During this journey the pair develops a bond – one similar to that of a father and son dynamic. Kikujiro says to a sleeping Masao that they are alike, right after Masao sees his mother. Later during the movie, we learn that Kikujiro’s own mother is in an elderly shelter when he goes there. But just like Masao earlier, Kikujiro only watches her from a distance before walking away. Wandering men, emotionally or otherwise, is a theme that keeps coming up in the movie – with Kikujiro and Masao both unable to stop seeking for an emotional fulfilment from their parental figures, while the aptly titled ‘Travelling Man’ endlessly wander the country in search of stories to fulfil his loneliness.

Pic. 07; Final shot of Kikujiro watching Masao running away.

Kikujiro is many things. He is irresponsible, impulsive, a Yakuza, a bully, and many more, but during the two hours that we spend with him, we see a slightly changed man. A little bit more empathetic, and a fatherly figure Masao desperately is seeking for. But above all, Kikujiro is a man who needs to be in therapy but is conditioned to not accept any external help with his emotional inadequacies – a broken man.

Masao and the Pains of Growing Up

Pic. 08; Masao and Kikujiro at the beach, shortly after seeing his mother. The angel bell can be seen on Kikujiro’s hands.

Although the titular character of the movie is not Masao, the narrative device of the film works from the perspective of his instead of it being from Kikujiro. It is apparent through two ways; one by sectioning off different portions of the movie with titles that Masao might write on his diary, and secondly by the way Kitano focus on not showing any act of violence on screen – we are shown the before and after, but never the violence itself (it being a departure for someone who primarily works on gangster films and portrays violence without pulling any punches).

If identities, including one’s own masculinity/ies, are developed during the due course of time and introspection, then Masao’s is the least developed by the virtue of him being a child with very little experience in those matters. It is a bit difficult to ascertain as to what kind of man he would grow up to be. Will he nostalgically cherry-pick Kikujiro’s Yakuza background as his ideal, or will he cherish the kind-hearted men who played with and entertained him during a time when he was inflicted with a life altering traumatic incident? Kitano and the film offers little insight into these matters – not by design, mind you. But because of the limitations put forth by the slice-of-life genre, and due to the small amount of time we spend with them.

Shy and reserved, Masao agrees with anything that another person might ask of him – extremely different from the character of Kikujiro. He makes no qualms with his travelling partner whenever they take a detour. He coasts along life without confronting anything – including his mother who abandoned him and his grandmother when he was a child. There is an expectation that comes with the road genre of films where the traveller comes against their end goal at least at the end of the film. Kitano denies that catharsis not only to the audience, but it extends to Masao as well.

Pic. 09; Masao cleans the blood off of Kikujiro’s face.

Earlier in the essay I wrote that Kikujiro becomes a surrogate father to Masao during the course of the film. Although that stays true, another case can be made for Masao taking care of the uncared child inside Kikujiro. I would go so far as to argue that Masao is almost as much a father figure to Kikujiro as is vice versa. Fatherhood is often seen as a pivotal point in the maturation of one’s masculinity. The responsibility of another individual is supposed to make him more ‘humane’. Kikujiro sleeps on the bench sitting next to Masao - who now takes the responsibility of a father, Masao finds a pharmacy and buys the necessary to give some level of comfort to Kikujiro. This act of kindness mellows Kikujiro quite a bit to Masao for the rest of the runtime.

Pic. 10; Masao playing with the rest of the Fatso, Baldie, and the Travelling Man.

All the people they encounter throughout the journey understand the introverted nature of Masao, and thus they try their best to entertain or engage with him throughout. There is never a moment where Masao feels left out. The impact left on him by the four men near the river cannot be understated. They appear in his dreams and are framed as days that will stick to him.

Pic. 11-12; Masao dreaming about the kind men.

Hisashi’s theme music plays in the background all the while Masao dreams about his four friends. Though they all try their best, none of them have a conversation with Masao outside cheering him up, and that again shows the inability of men to comfort others – not because they want it like that, but because their identities are socially constructed that way. Nonetheless, Masao is given a chance to mould his own masculinity/ies into something softer than most.

The Band of Three Merry-Men

Pic. 13; Kikujiro bullying the bikers to steal the angel bell.

The aesthetics of the characters Fatso and Baldie are that of the stereotypically aggressive bikers found elsewhere in mass media. But their personas are much softer than their appearance. Fatso complains about Kikujiro stealing his lucky charm angel bell given to him by girlfriend but does little in terms of action to obtain it back. They also keep mum when they find the bell on Masao’s hand, and ultimately let him keep it.

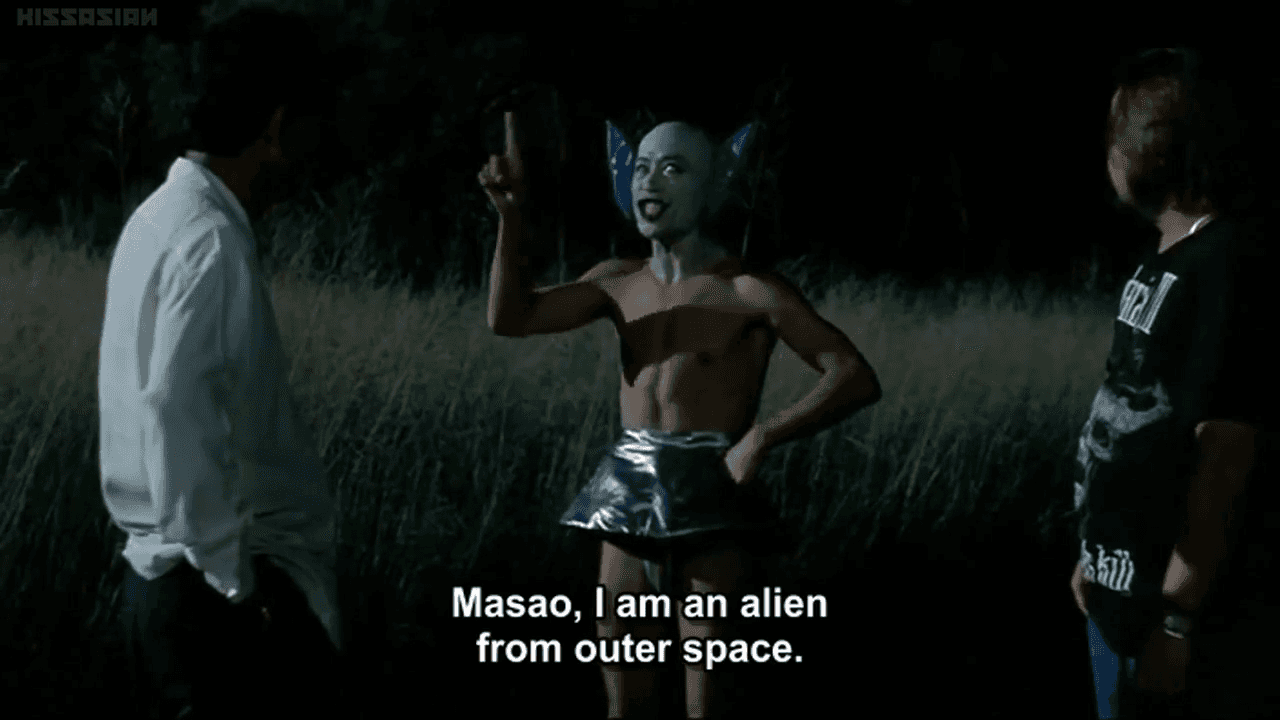

Pic. 14; Baldie cosplaying an alien to put on a show for Masao.

On top of subverting the biker persona, they also try their best to keep Masao company and go far lengths to keep him entertained and distract him from his trauma. But beyond that, none of the four men have any kind of conversation with him about what happened – most likely because they do not have any words of comfort or advice to pass on to him. The Travelling Man joins the other three in doing the same.

While Kikujiro makes fun of the biker duo, the film itself does not. Sure, they are comedic relief to a certain extent, but there is more to their characterisation than just that. They are framed as kind hearted people looking out for a lonely child.

Pic. 15; The gang bidding farewell.

Conclusion

Although bittersweet, the movie is ultimately a study on the positive impressions left on the next generation of men by action – whether it be that of violence or kindness. Earlier in the essay, I suggested that there is no way of knowing what kind of lessons Masao will take from this experience, and how this might sculpt his own masculinity/ies. But that is not entirely true. Kitano’s decision to ground the film mostly from Masao’s perspective, and him leaving out the violent acts outside his frame indicates that, Masao’s own masculinity/ies would be one of kindness – an amalgamation of the experiences that he had from the four kind men in his world.

The lucky charm angel bell which brings forth an angel whenever he is cornered, brought four angels to his aid, when he desperately needed it. By the end of the movie, all four of them, in turn, improves their own worldview, and alters their masculinity/ies to be a bit more mellow.

Men silently shouldering emotional burdens of other men, thus is the primary theme of the film. The prevalence of the same in the world around us is astounding. The inability to talk or make conversation about your insecurities and emotional trouble to the men around you, are something that most men are keenly aware of. Whether it be a father, a grandfather, or a male friend, men find it difficult to cross the invisible barrier. Grandfathers unable to express their wants for an emotional connection with their grandchildren, while they freely interact with their grandmothers is a sight that is all too common in our society. We don’t know how to breach the barrier that we desperately want to. The emotional burden that is left from this untold wants and needs puts a heavy tax on oneself. Thus, the catharsis that Kikujiro denies to the audience, and the lost look of Kikujiro himself during the final shot of his, is thematically relevant and strikes a tender chord for the men among its audience.